A saddle is a supportive structure for a rider of an animal, fastened to an animal’s back by a girth. The most common type is equestrian. However, specialized saddles have been created for oxen, camels and other animals.[1] It is not known precisely when riders first began to use some sort of padding or protection, but a blanket attached by some form of surcingle or girth was probably the first “saddle”, followed later by more elaborate padded designs. The solid saddle tree was a later invention, and though early stirrup designs predated the invention of the solid tree, the paired stirrup, which attached to the tree, was the last element of the saddle to reach the basic form that is still used today. Today, modern saddles come in a wide variety of styles, each designed for a specific equestrianism discipline, and require careful fit to both the rider and the horse. Proper saddle care can extend the useful life of a saddle, often for decades. The saddle was a crucial step in the increased use of domesticated animals, during the Classical Era.

Etymology

[edit]

The word “saddle” originates from the Old English word sadol which in turn comes from the Proto-Germanic language *sathulaz, with cognates in various other Indo-European languages,[2] including the Latin sella.[3]

Parts

[edit]

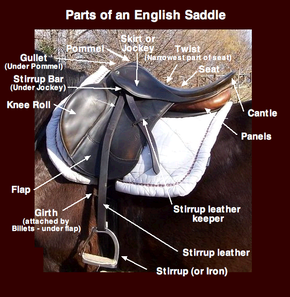

- Tree: the base on which the rest of the saddle is built – usually based on wood (or on a similar synthetic material). The saddler eventually covers it with leather or with a leather-like synthetic. The tree’s size determines its fit on the horse’s back, as well as the size of the seat for the rider. The tree supports and distributes the weight of the rider.[4]

- Seat: the part of the saddle where the rider sits. It is usually lower than the pommel and cantle – to provide security.

- Pommel (English)/ swells (Western) or saddlebow: the front, slightly raised area of the saddle.

- Cantle: the rear of the saddle

- Stirrup: part of the saddle in which the rider’s feet are placed; provides support and leverage to the rider.

- Leathers and flaps (English), or fenders (Western): The leather straps connecting the stirrups to the saddle tree and leather flaps giving support to the rider’s leg and protecting the rider from sweat.

- D-ring: a D-shaped ring on the front of a saddle, to which certain pieces of equipment (such as breastplates) can be attached.

- Girth or cinch: A wide strap that goes under the horse’s barrel, just behind the front legs of the horse, and holds the saddle on.

- Panels, lining, or padding: cushioning on the underside of the saddle.

Some saddles also include:

- Surcingle: A long strap that goes all the way around the horse’s barrel. Depending on purpose, may be used by itself, placed over a pad or blanket only, or placed over a saddle (often in addition to a girth) to help hold it on.

- Monkey grip or less commonly jug handle: a handle that may be attached to the front of European saddles or on the right side of Australian stock saddles. Riders may use it to help maintain their seat or to assist in mounting.

- Horn: knob-like appendage attached to the pommel or swells, most commonly associated with the modern western saddle, but seen on some saddle designs in other cultures.

- Knee rolls: Seen on some English and Australian saddles, extra padding on the front of the flaps to help stabilize the rider’s leg. Sometimes thigh rolls are also added to the back of the flap.

History and development

[edit]

There is evidence, though disputed, that humans first began riding the horse not long after domestication, possibly as early as 4000 BC.[5] The earliest saddle known thus far was discovered inside a woman’s tomb in the Turpan basin, in what is now Xinjiang, China, dating to between 727–396 BC.[6] The saddle is made of cushioned cow hide, and shows signs of usage and repair.[6] The tomb is associated with the Subeixi Culture, which is associated with the Jushi Kingdom described in later Chinese sources.[6] The Subeixi people had contact with Scythians, and share a similar material culture with the Pazyryk culture, where later saddles were found.[6]

Eurasian and Northern Asian nomads on the Mongolian plateau developed an early form of saddle with a rudimentary frame, which included two parallel leather cushions, with girth attached to them, a pommel and cantle with detachable bone/horn/hardened leather facings, leather thongs, a crupper, breastplate, and a felt shabrack adorned with animal motifs. These were located in Pazyryk burials finds.[7] These saddles, found in the Ukok Plateau, Siberia were dated to 500-400 BC.[8][9] Iconographic evidence of a predecessor to the modern saddle has been found in the art of the ancient Armenians, Assyrians, and steppe nomads depicted on the Assyrian stone relief carvings from the time of Ashurnasirpal II. Some of the earliest saddle-like equipment were fringed cloths or pads used by Assyrian cavalry around 700 BC. These were held on with a girth or surcingle that included breast straps and cruppers. From the earliest depictions, saddles became status symbols. To show off an individual’s wealth and status, embellishments were added to saddles, including elaborate sewing and leather work, precious metals such as gold, carvings of wood and horn, and other ornamentation. The Scythians also developed an early saddle that included padding and decorative embellishments.[8] Though they had neither a solid tree nor stirrups, these early treeless saddles and pads provided protection and comfort to the rider, with a slight increase in security. The Sarmatians also used a padded treeless early saddle, possibly as early as the seventh century BC[10] and ancient Greek artworks of Alexander the Great of Macedon depict a saddle cloth.[8] The Greeks called the saddlecloth or pad, ephippium (ἐφίππιον or ἐφίππειον).[11]

Early solid-treed saddles were made of felt that covered a wooden frame. Chinese saddles are depicted among the cavalry horses in the Terracotta Army of the Qin dynasty, completed by 206 BC.[12] Asian designs proliferated during China‘s Han dynasty around approximately 200 BC.[8] One of the earliest solid-treed saddles in the Western world was the “four horn” design, first used by the Romans as early as the 1st century BC.[13] Neither design had stirrups.[8] Recent archeological finds in Mongolia (e.g. Urd Ulaan Uneet site) suggest that the Mongolic Rouran tribes had sophisticated, wooden frame saddles as early as the 3rd century AD.[14] The wooden frame saddle found at the Urd Ulaan Uneet site in Mongolia is one of the earliest examples found in Central and East Asia.[15]

The development of the solid saddle tree was significant; it raised the rider above the horse’s back, and distributed the rider’s weight on either side of the animal’s spine instead of pinpointing pressure at the rider’s seat bones, reducing the pressure (force per unit area) on any one part of the horse’s back, thus greatly increasing the comfort of the horse and prolonging its useful life. The invention of the solid saddle tree also allowed development of the true stirrup as it is known today.[16] Without a solid tree, the rider’s weight in the stirrups creates abnormal pressure points and makes the horse’s back sore. Thermography studies on “treeless” and flexible tree saddle designs have found that there is considerable friction across the center line of a horse’s back.[17]

The stirrup was one of the milestones in saddle development. The first stirrup-like object was invented in India in the 2nd century BC, and consisted of a simple leather strap in which the rider’s toe was placed. It offered very little support, however. Mongolic Rouran tribes in Mongolia are thought to have been the inventors of the modern stirrup, but the first dependable representation of a rider with paired stirrups was found in China in a Jin Dynasty tomb of about 302 AD.[18] The stirrup appeared to be in widespread use across China by 477 AD,[19] and later spread to Europe. This invention gave great support for the rider, and was essential in later warfare.

Post-classical West Africa

[edit]

Accounts of the cavalry system of the Mali Empire describe the use of stirrups and saddles in the cavalry. Stirrups and saddles brought about innovation in new tactics, such as mass charges with thrusting spears and swords.[20]

Middle Ages

[edit]

Main article: Horses in the Middle Ages

Saddles were improved upon during the Middle Ages, as knights needed saddles that were stronger and offered more support. The resulting saddle had a higher cantle and pommel (to prevent the rider from being unseated in warfare) and was built on a wooden tree that supported more weight from a rider with armor and weapons. This saddle, a predecessor to the modern Western saddle, was originally padded with wool or horsehair and covered in leather or textiles. It was later modified for cattle tending and bullfighting in addition to the continual development for use in war. Other saddles, derived from earlier, treeless designs, sometimes added solid trees to support stirrups, but were kept light for use by messengers and for horse racing.

Modernity

[edit]

The saddle eventually branched off into different designs that became the modern English and Western saddles.

One variant of the English saddle was developed by François Robinchon de la Guérinière, a French riding master and author of “Ecole de Cavalerie” who made major contributions to what today is known as classical dressage[citation needed]. He put great emphasis on the proper development of a “three point” seat that is still used today by many dressage riders.

In the 18th century, fox hunting became increasingly popular in England. The high-cantle, high-pommel design of earlier saddles became a hindrance, unsafe and uncomfortable for riders as they jumped. Due to this fact, Guérinière’s saddle design which included a low pommel and cantle and allowed for more freedom of movement for both horse and rider, became increasingly popular throughout northern Europe. In the early 20th century, Captain Frederico Caprilli revolutionized the jumping saddle by placing the flap at an angle that allowed a rider to achieve the forward seat necessary for jumping high fences and traveling rapidly across rugged terrain[citation needed].

The modern Western saddle was developed from the Spanish saddles that were brought by the Spanish Conquistadors when they came to the Americas[citation needed]. These saddles were adapted to suit the needs of vaqueros and cowboys of Mexico, Texas and California, including the addition of a horn that allowed a lariat to be tied or dallied for the purpose of holding cattle and other livestock.

Types

[edit]

In the Western world there are two basic types of saddles used today for horseback riding, usually called the English saddle and the “stock” saddle. The best known stock saddle is the American western saddle, followed by the Australian stock saddle. In Asia and throughout the world, there are numerous saddles of unique designs used by various nationalities and ethnic groups.

English

[edit]

Main article: English saddle

English saddles are used for English riding throughout the world, not just in England or English-speaking countries. They are the saddles used in all of the Olympic equestrian disciplines. The term English saddle encompasses several different styles of saddle, including those used for eventing, show jumping and hunt seat, dressage, saddle seat, horse racing, horse surfing and polo.

The major distinguishing feature of an English saddle is its flatter appearance, the lack of a horn, and the self-padding design of the panels: a pair of pads attached to the underside of the seat and filled with wool, foam, or air. However, the length and angle of the flaps, the depth of the seat and height of the cantle all play a role in the use for which a particular saddle is intended.

The “tree” that underlies the saddle is usually one of the defining features of saddle quality. Traditionally, the tree of an English saddle is built of laminated layers of high quality wood reinforced with spring steel along its length, with a riveted gullet plate. These trees are semi-adjustable and are considered “spring trees”. They have some give, but a minimum amount of flexibility.

More recently, saddle manufacturers are using various materials to replace wood and create a synthetic molded tree (some with the integrated spring steel and gullet plate, some without). Synthetic materials vary widely in quality. Polyurethane trees are often very well-made, but some cheap saddles are made with fiberglass trees of limited durability. Synthetic trees are often lighter, more durable, and easier to customize. Some designs are intended to be more flexible and move with the horse.

Several companies offer flexible trees or adjustable gullets that allow the same saddle to be used on different sizes of horses.

Stock

[edit]

Main article: Western saddle

Main article: Australian Stock Saddle

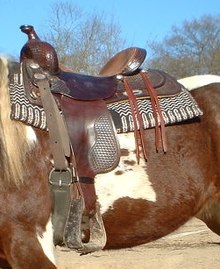

Western saddles are saddles originally designed to be used on horses on working cattle ranches in the United States. Used today in a wide variety of western riding activities, they are the “cowboy saddles” familiar to movie viewers, rodeo fans, and those who have gone on tourist trail rides. The Western saddle has minimal padding of its own, and must be used with a saddle blanket or pad in order to provide a comfortable fit for the horse. It also has sturdier stirrups and uses a cinch rather than a girth. Its most distinctive feature is the horn on the front of the saddle, originally used to dally a lariat when roping cattle.

Other nations such as Australia and Argentina have stock saddles that usually do not have a horn, but have other features commonly seen in a western saddle, including a deep seat, high cantle, and heavier leather.

The tree of a western saddle is the most critical component, defining the size and shape of the finished product. The tree determines both the width and length of the saddle as it sits on the back of the horse, as well as the length of the seat for the rider, width of the swells (pommel), height of cantle, and, usually, shape of the horn. Traditional trees were made of wood or wood laminate covered with rawhide and this style is still manufactured today, though modern synthetic materials are also used. The rawhide is stretched and molded around the tree, with minimal padding between the tree and the exterior leather, usually a bit of relatively thin padding on the seat, and a sheepskin cover on the underside of the skirts to prevent chafing and rubbing on the horse.

Though a western saddle is often considerably heavier than an English saddle, the tree is designed to spread out the weight of the rider and any equipment the rider may be carrying so that there are fewer pounds per square inch on the horse’s back and, when properly fitted, few if any pressure points. Thus, the design, in spite of its weight, can be used for many hours with relatively little discomfort to a properly conditioned horse and rider.

Military

[edit]

British Universal Pattern military saddles were used by the mounted forces from Australia, Britain, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa.[21][better source needed]

The Steel Arch Universal Pattern Mark I was issued in 1891. This was found to irritate riders and in 1893 it was discontinued in favour of the Mark II. In 1898, the Mark III appeared, which had the addition of a V-shaped arrangement of strap billets on the sideboards for the attachment of the girth. This girthing system could be moved forward or back to obtain an optimum fit on a wide range of horses.

From 1902 the Universal Military Saddle was manufactured with a fixed tree, broad panels to spread the load, and initially a front arch in three sizes. The advantage of this saddle was its lightness, ease of repair and comfort for horse and rider. From 1912 the saddle was built on an adjustable tree and consequently only one size was needed. Its advantage over the fixed tree 1902 pattern was its ability to maintain a better fit on the horse’s back as the horse gained or lost weight. This saddle was made using traditional methods and featured a seat blocked from sole leather, which maintained its shape well.[22] [better source needed] Military saddles were fitted with metal staples and dees to carry a sword, spare horse shoes and other equipment.

In the US, the McClellan saddle was introduced in the 1850s by George B. McClellan for use by the United States Cavalry, and the core design was used continuously, with some improvements, until the 1940s.[23] Today, the McClellan saddle continues to be used by ceremonial mounted units in the U.S. Army. The basic design that inspired McClellan saw use by military units in several other nations, including Rhodesia and Mexico, and even to a degree by the British in the Boer War.

Military saddles are still produced and are now used in exhibitions, parades and other events.

Asian

[edit]

Saddles in Asia date to the time of the Scythians[24] and Cimmerians.[25] Modern Asian saddles can be divided into two groups: those from nomadic Eurasia, which have a prominent horn and leather covering, and those from East Asia, which have a high pommel and cantle. Central Asian saddles are noted for their wide seats and high horns. The saddle has a base of wood with a thin leather covering that frequently has a lacquer finish. Central Asian saddles have no pad and must be ridden with a saddle blanket. The horn comes in particular good use during the rough horseback sport of buskashi, played throughout Central Asia, which involves two teams of riders wrestling over a decapitated goat’s carcass.

In the Near East, a saddle large enough to carry more than one person is called a howdah which is fitted on elephants. Some of the largest examples of a saddle, elaborate howdah were used in warfare outfitted with weaponry, and alternatively for monarchs, maharajahs, and sultans.

Howdahs continue to play a role in modern Indian ceremonies. In recent years, the elephant chosen to carry the Golden Howdah has been contentious and newsworthy. In 2020, the elephant Arjuna was deemed too old to carry the Golden Howdah after a Supreme Court and Union Government guideline stated that elephants over the age of 60 could no longer serve in this role. A younger, 54 year old elephant, Abhimanyu, was chosen to carry out the duty instead. In preparation for carrying the Golden Howdah, Abhimanyu’s strength and endurance was tested by carrying a large wooden howdah.[26]

Saddles from East Asia differ from Central Asian saddles by their high pommel and cantle and lack of a horn. East Asian saddles can be divided into several types that are associated with certain nationalities and ethnic groups. Saddles used by the Han Chinese are noted by their use of inlay work for ornamentation. Tibetan saddles typically employ iron covers inlaid with precious metals on the pommel and cantle and universally come with padding. Mongolian saddles are similar to the Tibetan style except that they are typically smaller and the seat has a high ridge. Saddles from ethnic minority groups in China’s southwest, such as in Sichuan and Yunnan provinces, have colorful lacquer work over a leather covering.[citation needed]

Japanese

[edit]

Main article: Kura (saddle)

Japanese saddles are classified as Chinese-style (

‹The template below is included via a redirect (Template:Transl) that is under discussion. See redirects for discussion to help reach a consensus.›

karagura) or Japanese-style (

‹The template below is included via a redirect (Template:Transl) that is under discussion. See redirects for discussion to help reach a consensus.›

yamatogura). In the Nara period the Chinese style was adopted. Gradually the Japanese changed the saddle to suit their needs, and in the Heian period, the saddle typically associated with the samurai class was developed. These saddles, known as kura, were lacquered as protection from the weather. Early samurai warfare was conducted primarily on horseback and the kura provided a rugged, stable, comfortable platform for shooting arrows, but it was not well suited for speed or distance. In the Edo period horses were no longer needed for warfare and Japanese saddles became quite elaborate and were decorated with mother of pearl inlays, gold leaf, and designs in colored lacquer.[27][28]

Other

[edit]

- Sidesaddle, designed originally as a woman’s saddle that allowed a rider in a skirt to stay on and control a horse. Sidesaddle riding is still seen today in horse shows, fox hunting, parades and other exhibitions.

- Trick (or stunt) riding saddles are similar to western saddles and have a tall metal horn, low front and back, reinforced hand holds and extended double rigging for a wide back girth.

- Endurance riding saddle, a saddle designed to be comfortable to the horse with broad panels but lightweight design, as well as comfortable for the rider over long hours of riding over challenging terrain.

- Police saddle, similar to an English saddle in general design, but with a tree that provides greater security to the rider and distributes a rider’s weight over a greater area so that the horse is comfortable with a rider on its back for long hours.

- McClellan saddle, a specific American cavalry model that entered service just before the Civil War with the United States Army. It was designed with an English-type tree, but with a higher pommel and cantle. Also, the area upon which the rider sits was divided into two sections with a gap between the two panels.[29]

- Pack saddle, similar to a cavalry saddle in the simplicity of its construction, but intended solely for the support of heavy bags or other objects being carried by the horse.

- Double seat saddles have two pairs of stirrups and two deep padded seats for use when double-banking or riding double with a child behind an adult rider. The western variety has one horn on the front of the saddle.

- Treeless saddles are available in both Western and English designs and are not built upon a solid saddle tree. They are intended to be flexible and comfortable on a variety of horses, but do not always provide the weight support that a solid tree does. The use of an appropriate saddle pad is essential for treeless saddles.

- A flexible saddle uses a traditional tree, but the panels are not permanently attached to the finished saddle. These saddles use flexible panels (the part that sits along the horse’s back) that are moveable and adjustable to provide a custom fit for the horse and allow for changes of placement as the horse’s body develops.

- Although there is not one specific kind, therapy saddles that aid in the riding experience of those who are taking part in Equine Assisted Therapy are made to fit differing individuals according to their needs. Typically, these saddles are made of soft materials and allow the rider to sit closer to the back of the animal, which in turn transfers the horse’s heat to the rider to allow for muscle relaxation and stimulation.[30]

- Bareback pad, usually a simple pad in the shape of an English-style saddle pad, made of cordura nylon or leather, padded with fleece, wool or synthetic foam, equipped with a girth. It is used as an alternative to bareback riding to provide padding for both horse and rider and to help keep the rider’s clothing a bit cleaner. Depending on materials, bareback pads offer a bit more grip to the rider’s seat and legs. However, though some bareback pads come with handles and even stirrups, without being attached to a saddle tree, these appendages are unsafe and pads with them should be avoided. In some cases, the addition of stirrups without a supporting tree place pressure on the horse’s spinous processes, potentially causing damage.

Fitting

[edit]

Main articles: English saddle and Western saddle

A saddle, regardless of type, must fit both horse and rider.[31] Saddle fitting is an art and in ideal circumstances is performed by a professional saddle maker or saddle fitter. Custom-made saddles designed for an individual horse and rider will fit the best, but are also the most expensive. However, many manufactured saddles provide a decent fit if properly selected, and some minor adjustments can be made.

The definition of a fitting saddle is still controversial; however, there is a vital rule for fitting that no damage should occur to the horse’s skin and no injury should be presented to any muscular or neural tissues beneath the saddle.[32]

Width of the saddle is the primary means by which a saddle is measured and fitted to a horse, though length of the tree and proper balance must also be considered. The gullet of a saddle must clear the withers of the horse, but yet must not be so narrow as to pinch the horse’s back. The tree must be positioned so that the tree points (English) or bars (Western) do not interfere with the movement of the horse’s shoulder. The seat of the saddle must be positioned so that the rider, when riding correctly, is placed over the horse’s center of balance. The bars of the saddle must not be so long that they place pressure beyond the last rib of the horse. A too-short tree alone does not usually create a problem, as shorter trees are most often on saddles made for children, though a short tree with an unbalanced adult rider may create abnormal pressure points.

While a horse’s back can be measured for size and shape, the saddle must be tried on the individual animal to assure proper fit. Saddle blankets or pads can provide assistance to correct minor fit problems, as well as provide comfort and protection to the horse’s back, but no amount of padding can compensate for a poor-fitting saddle. For example, saddles that are either too wide or too narrow for the horse will cause change in pressure points and ultimately muscle atrophy in the epaxial muscles.[33] The common problems associated with saddle fitting are: bridging, ill-fitting headplates and incorrect stuffing of the panels.[32]

Saddle-related injuries

[edit]

Contact-point injuries

[edit]

Depending on the rider, the saddle may need to be adjusted or replaced entirely to ensure proper fitment. Riding a saddle that doesn’t properly secure and balance the rider can cause pain in the hips and back, as well as saddle sores under the bones that make contact with the saddle during riding.[34]

Saddle-horn injury

[edit]

On horseback, a rider’s pelvis may receive a saddle-horn injury due to falling onto the saddle after being bounced into the air.[35] The strikes against the saddle’s horn compress the pelvic ring, which can lead to further complications such as pubic symphysis or injury to the sacroiliac joint.[36]